A Summer of CS50 in Ethiopia

Vivek Jayaram Sept 1, 2017

Several weeks back, I returned from a two-month teaching project in Ethiopia. It was a crazy and hectic time, but also one of my most interesting and eye-opening experiences. For those who remember, when I returned from Switzerland after studying abroad, every other sentence of mine began something like “well in Switzerland they…”. It’s been somewhat similar this time where I make sure everyone knows about Ethiopia, from their world heritage sites to their new infrastructure projects. My worldview continues to be shaped by experiences in countries all over the world, and here are some of the main takeaways from Ethiopia along with a few funny stories from my time there.

Why CS50?

Broadly speaking, the project aimed to implement CS50 as the standard introductory CS course at universities across Ethiopia. For those who don’t know, CS50 is the introductory programming course at Harvard that regularly has over 700 students. Although there are many courses that could be used for intro CS, a major problem in Ethiopia is the lack of fast and reliable internet at universities. CS50 was particularly suitable for this because the various components could all be packaged and taught in an offline way. These include videotaped lectures, automated grading software, and homework walkthroughs. In fact, starting in 2016, even students at Harvard no longer attended physical lectures by David Malan, but watched them online. Therefore, our value proposition to Ethiopian Universities was that after training some staff members to be CS50 TFs, first-year students in Ethiopia would receive a CS education comparable to first-year students at Harvard. (Is the $60,000/year for Harvard really worth it then?)

We didn’t want to teach CS50 only to undergraduates; that would only have limited impact. Instead, we were training instructors from various universities to become qualified CS50 TFs, with the hope that they could offer the course to undergraduates and spread it to other universities after we left. These instructors weren’t PhD level professors, but most had finished a bachelor or master’s degree in Ethiopia and were between 25-35 years old. Since I was the only available TF from Harvard, I got my high school friend and fellow CS student Stephen McAleer to join. The experience was much more fun with him, and I probably would have gone crazy if I was there by myself for 8 weeks. After arranging all the logistics and dates, we set off on an Ethiopian Airlines flight from SFO to Addis Ababa with some CS50 shirts and USB sticks filled with hours of lectures and problem sets.

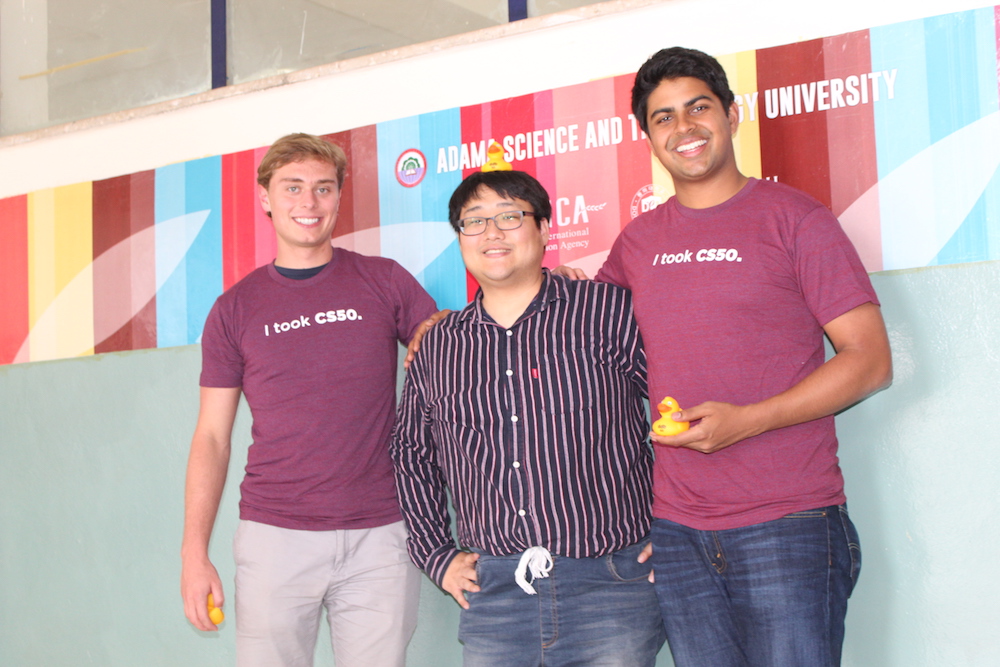

The group of instructors who took CS50

Why Ethiopia?

Ethiopia has been making huge strides in development, particularly in education, thanks to an extended period of stability and government spending. The previously military junta government fell in 1991 and was replaced by a US backed regime that still rules today. Although the current government is by no means democratic, the stability has allowed large amounts of growth. In 2017 Ethiopia had the highest GDP growth of any country at 8.3%. They also have one of the highest spending rates on infrastructure and education as a fraction of GDP, but official numbers are hard to find. The project was first proposed by Dr. Munib Wober, a visiting professor at Harvard of Ethiopian origin. He was working with the ministry of science and technology, and was able to help arrange all the funding for this trip to pay for our flights, accomodation, food, and transporation.

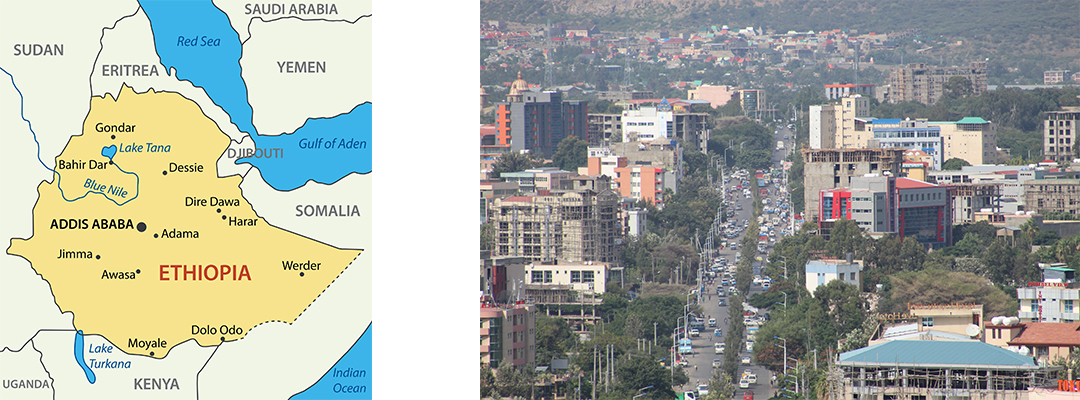

A map of Ethiopia, along with the view of Adama from the top of a hill. Adama is just below the capital city Addis Ababa.

The university where we taught was called Adama Science and Technology University (ASTU). It was founded in 1993 and is located a little more than an hour south of the capital Addis Ababa. Given its recentness, the university lacked a lot of necessary infrastructure, such as wet lab materials, qualified professors, or fast internet. Imagine trying to start a university from scratch. Almost none of the teaching staff had PhDs, and those who did were often in positions of admnisitration. The lack of professors seemed to be the main obstacle for turning ASTU into a world class research university. In order to bootstrap their education system, they have been spending large amounts of money to partner with foreign institutions and bring foreign instructors for limited periods of time. Of course most professors from western universities would not be willing to sacrifice a semester to teach in a university with fewer facilities, so this still remains a difficulty. The Ethiopian instructors taking CS50 were expecting someone of the caliber of David Malan to come run the program, so I think they were a little disappointed to see a couple of 22 year olds who didn't even have masters degrees. There were also a few Germans teaching before us, and during our stay there were a number of Koreans working on improving IT infrastructure through their KOICA project. A lot of the existing course curriculum was also borrowed from foreign universities, such as a C++ programming class from Dong-Eui university in Korea, or a several Engineering courses borrowed from MIT.

"Dragon" Kim, a member of the Koica Project. When asked why he goes by Dragon he said: In Korea we have 5 million people. But 10 million are named Kim.

Conditions in the Classroom

There were many uncertainties before we left. How good was the internet? How qualified were the instructors? Would they find CS50 too easy or too hard? Would English language knowledge be a problem? Only after we arrived did we really understand how to best tailor the course based on the various uncertainties. We were worried about access to computers, but we taught in computer lab of 30 Windows 7 desktop machines installed by the KOICA project. It really reminded me of a computer lab you might find in a US high school. It turns out there was internet access in the university, but it was slow and the power would frequently cut out for large portions of the day. Sometimes I would be in the middle of a presentation, when the power would cut so we would decide to end class early. In addition, some instructors also came from up to 90 miles away, so when it would rain we would often delay or cancel class because the roads were too bad for everyone to attend (it didn't help that summer is their rainy season).

However, the instructors had figured out ways to get around many of the limitations that were present. For example, one student found good internet connection in the city and downloaded all of Wikipedia onto a hard drive (100+ GB). Another student downloaded every C++ stack overflow help article so he could look up common coding issues without internet (3+ TB)! Students were also interested in machine learning research, but without internet or high performance computers research in ML is almost impossible. Instead, I was working with them to turn the 30 computer lab desktop machines into a single giant distributed system that could run tensorflow. This made me realize how much we take certain things for granted, like Wikipedia, but also convinced me that if you’re determined enough then you can get around situational limitations.

The computer lab where class was held

The program overall was a mixed success. We planned on teaching 30 instructors, but only 10 finished the course for a variety of reasons, such as other commitments or a lack of motivation. Some instructors found CS50 too easy, so we ended up interleaving a variety of other advanced topics such as machine learning, systems programming, and advanced algorithms. The university also expressed hesitation about offering CS50 to undergrads because they have few measures to prevent cheating like copying psets or looking up answers online. Currently, all classes at ASTU are graded through final examination only where cheating is not possible. However, we tried to convince the CS department that homework assignments in generaly are necessary for learning for computer science, even if there is a greater risk for cheating. We still hope to offer the course at Addis Ababa Science and Technology University and provide them support as they teach the course. You can read more about the CS50 aspect of the program on our official CS50 blog post (coming soon).

Outside the Classroom

In addition to providing great teaching experience, the program also gave me the opportunity to explore a new country I knew little about. This was made more exciting by the fact that I couldn't find too much information online before going. Nowadays, if something isn’t online then does it exist anyway? Before arriving, I hardly found any pictures of the university, the town, or my hotel. In addition, very few local places had any kind of online presence. But the lifestyle is of course suited to this and can sometimes be surprising. For example, even though Google maps some locations in Addis Ababa, most people don't trust it. I was trying to meet up with fellow Harvard student Franci van Rhyn in Addis Ababa, and although Google maps showed us exactly where to go, the driver refused to follow it. He kept saying “No Google maps, people maps! People maps!” as we confusedly circled around the neighborhood continually asking people on the street for directions. During another weekend trip, we wanted to make a reservation at the best possible hotel in one of the smaller Ethiopian towns in the mountains. We weren’t able to find the phone number for the hotel online, but one of our students had a friend from that town. So he called that friend who drove to the hotel, asked for the number, and sent it back to us so we could make a reservation. The default method of finding information or accomplishing a task was always to go through people rather than the internet.

The variety of landscapes we saw in a single day's drive

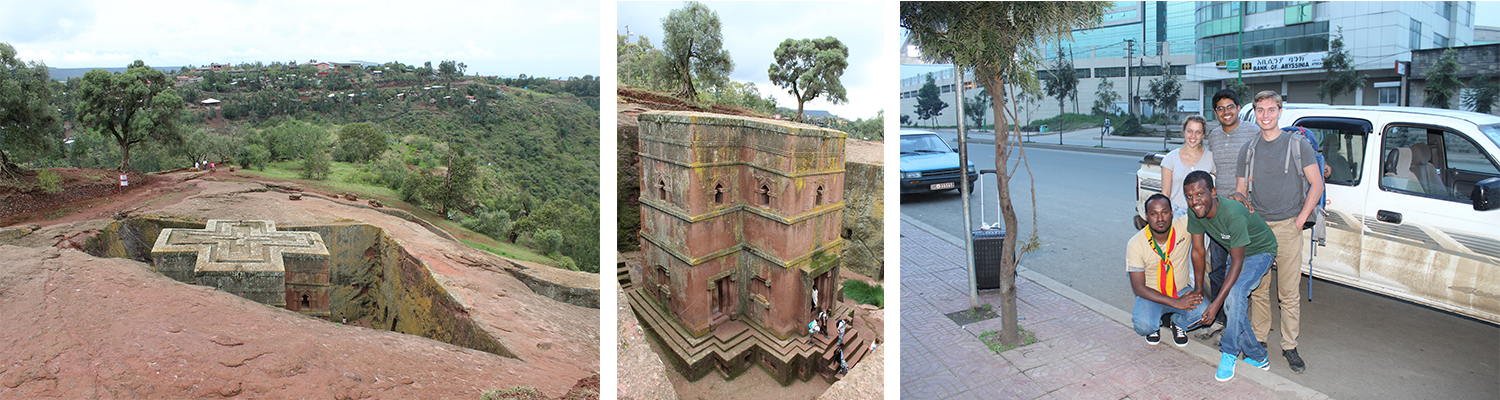

The lack of available information online also means that there are many misconceptions about Ethiopia. For example, at first I was expecting to find a dry, dusty, and hot place. However, the mountain ranges that weave through Ethiopia cause a wide variety of climates, from desert, to jungles, to rolling fields. Our trip to Lalibela, a city of ancient churches, took us through all the extremes of terrain. As we headed east from Adama, we passed through the Somali region of Ethiopia where not a single plant grew, and nomads on camels trekked over the parched ground. But as we headed north and gained elevation, we saw breathtaking views and many villages nestled in the mountainside. Unfortunately, we got stuck in the middle of nowhere with car problems and rain, so we had to spend the night in a the most remote village you can imagine. There was no hotel, but we paid $4 to stay in a guesthouse without running water and a hole in the ground for a toilet. When we finally reached Lalibela the following day, it was an amazing site like something straight out of an Indiana Jones movie. There were a number of churches that had been carved straight out of the rock a thousand years ago, which were almost 100 feet high. The extreme remoteness of the city was also a nice change from the overcrowded tourist locations I had previously visited.

The rock carved churches of lalibela (top view and front view of the same church)

Safety

Many westerners also have misconceptions regarding the safety of a country like Ethiopia. Although there are definitely incidents from time to time, particularly from militant groups in Somalia, the country as a whole felt extremely safe. The authoritarian government maintains a strong network of security to prevent terrorism, banditry, or other kinds of violence against foreigners. One surprising thing we discovered is that it is almost impossible to own a gun in Ethiopia. In fact, a look at gun ownership per country shows that the US is first by far, with 118 guns per 100 people, while Ethiopia is fifth to last with 0.4 guns per 100 people . And these were almost entirely restricted to military personnel. Although petty crime like pickpocketing was common, it’s no surprise that we had no problems with safety.

A soldier and kid in front of a monument. I love the juxtaposition here.

This security does come at a cost, however. As gun-loving Americans will tell you, banning guns is one of the key things an authoritarian government will do to keep power. This was definitely the case in Ethiopia. Under the surface of stability, security, and GDP growth in Ethiopia, lay the reality of human rights issues that we saw briefly during our travels in the Oromo Region. Ethiopia is made up of numerous ethnic groups, but the Tigray ethnic group currently controls the government, even though they only constitute 6% of the population. It is widely known that the elections are non-democratic, with the suppression of opposing parties, and other kinds of electoral fraud. In 2016, members of the Oromo ethnic group staged protests regarding this lack of representation and ethnic discrimination. While we were in the country, there was another protest over high taxes on farmers, which led to the government declaring a state of emergency in parts of Oromia. Unfortunately, this was also when we decided to go hiking through the Bale Mountains in Oromia. We went with two students from the university, but were unware that there was a curfew on travel between towns after dark. We had gone for dinner in a neighboring town, only 5 miles from our hotel, but as we tried to go back, we were stopped by a roadblock that had been set up after dark. The pickup truck of the guard pulled us over, but our driver explained that we were foreign professors, on special invitation from the government, and we were not part of any protests. They let us pass, but had we been local Ethiopians, the situation would not have ended up in our favor.

Conclusion

All in all, the 8 weeks there was an amazing time that gave us the ability to explore a new country, gain valuable teaching and leadership experience, and help improve university education in Ethiopia. Throughout the whole trip we were treated extremely well by the university. They paid for our flights and put us in a quality hotel where the food was also covered. We were also able to travel and visit sites such as the Lalibela rock churches, the walled city of Harar, and the Masai Mara game reserve in Kenya. This partnership with ASTU is something that we hope to keep up in the future by sending more Harvard students to Ethiopia to teach a variety of subjects.

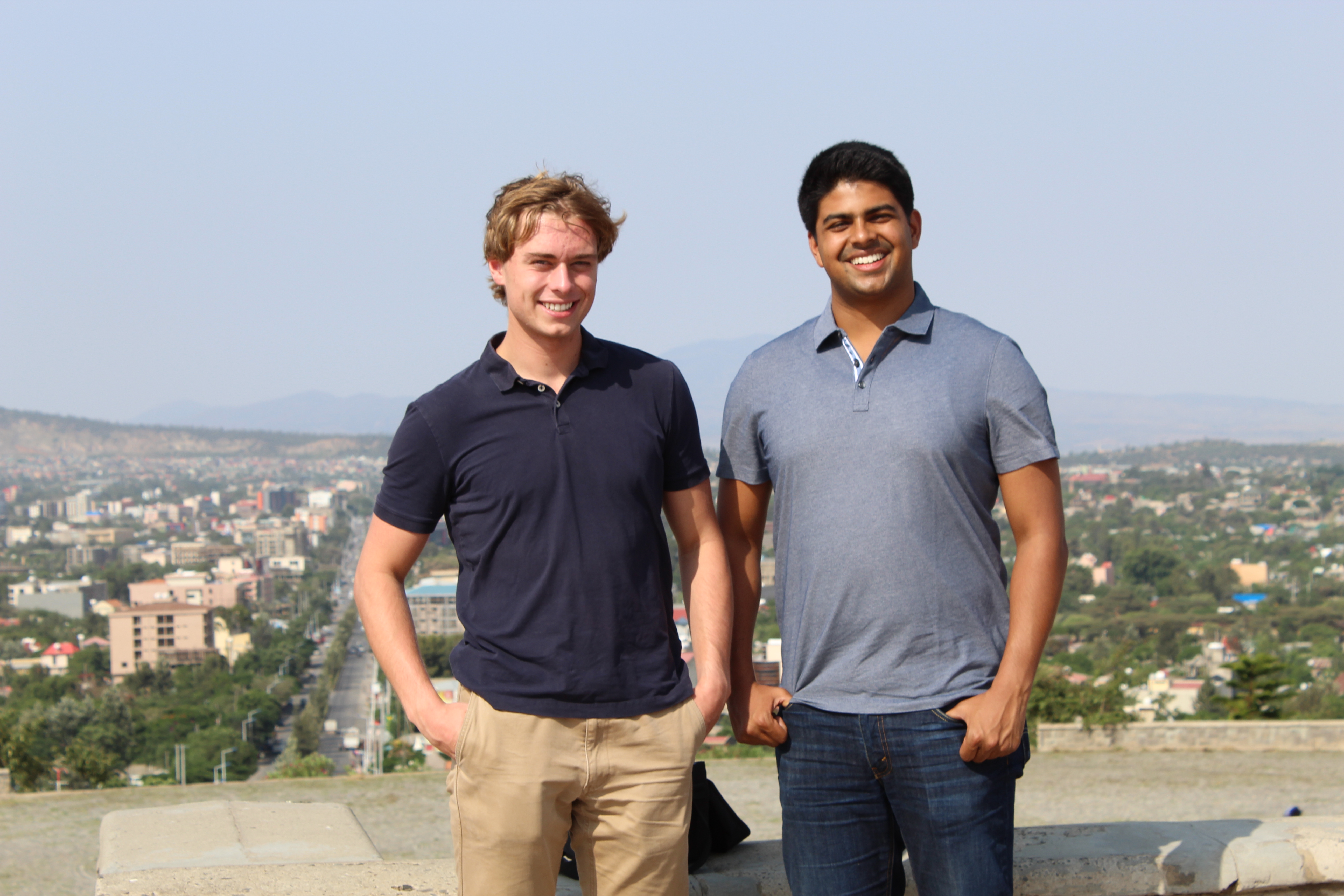

Standing on the top of a hill in Adama